Parallelization

1 Parallel Computing

1.1 What is Parallel Computing?

1.1.1 Sequential Computing

Historical context:

- Software traditionally written for sequential execution

- Single CPU executes instructions one at a time, in order

- Next instruction only starts after previous one completes

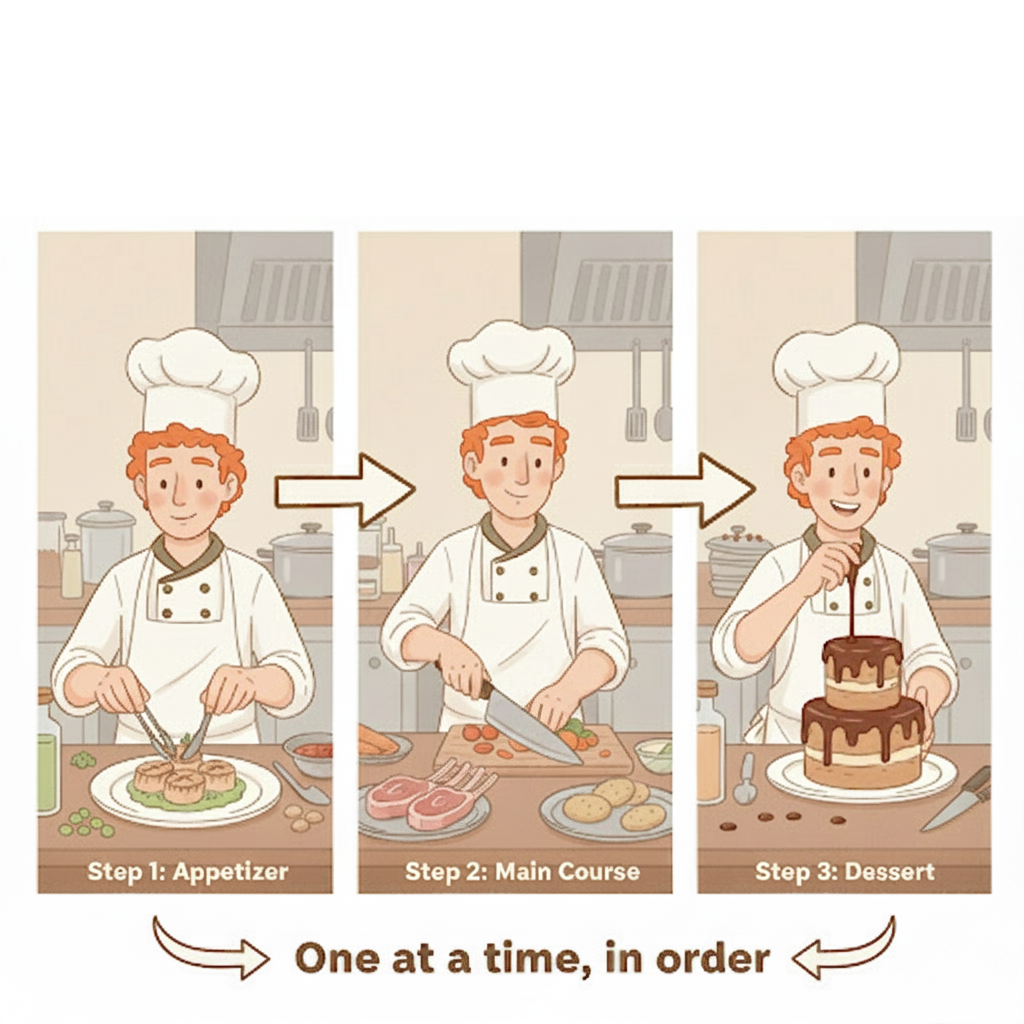

Analogy: Single chef preparing a three-course meal must finish appetizer completely before starting main course, then dessert.

1.1.2 Concurrency vs. Parallelism

Critical distinction for Python performance:

Concurrency:

- Managing multiple tasks at once

- Single worker rapidly switches between tasks

- Creates illusion of simultaneous execution

- Multiple tasks “in progress” but only one actively worked on

Analogy: One chef making soup and steak, puts soup to simmer, sears steak while soup cooks, switches back to stir soup.

1.1.3 Parallel Computing

Core concept:

- Simultaneous use of multiple processing elements for one problem

- Large task broken into smaller, independent sub-tasks

- Sub-tasks executed concurrently on different processors

- Results combined for final solution

Analogy: Head chef brings two assistants, three separate stations working simultaneously on appetizer, main course, and dessert. Meal ready in fraction of the time.

Parallelism:

- Executing multiple tasks at exact same time

- Requires multiple physical workers (processor cores)

- True simultaneous execution

1.2 CPU Architecture

1.2.1 CPU Components

Main parts:

- Control Unit (CU): Manages data flow and coordinates CPU actions

- Arithmetic Logic Unit (ALU): Performs mathematical operations and logical comparisons

- Registers: Small, fast memory locations inside CPU for current data/instructions

1.2.2 Multi-core Processors

Definition:

- Single CPU chip with 2+ independent processing units (cores)

- Each core has own CU, ALU, and registers

- Functions as independent CPU

- Enables true simultaneous instruction execution

Physical vs. Logical Cores:

Physical Cores:

- Real, tangible processing units in CPU

- Source of true parallelism

- Example: Quad-core = four separate, complete processing units

Logical Cores:

- Software abstraction via Hyper-Threading/SMT

- Makes one physical core appear as two to OS

- Uses idle parts of physical core simultaneously

- Performance boost: ~20-30%, not double

- Example: One thread uses math unit while another uses memory unit

1.3 Python-Specific Challenges

1.3.1 The Global Interpreter Lock (GIL)

What it is:

- Lock in CPython interpreter

- Only one thread executes Python bytecode at any moment

- Problem for CPU-bound tasks

1.3.2 Multithreading (One Kitchen, Many Chefs)

The setup:

- Python program = one kitchen

- Threads = chefs in that kitchen

- Shared memory = tools and ingredients

The problem:

- GIL = strict rule: only one chef in kitchen at a time

- Multiple threads work concurrently, not in parallel

- Can’t utilize multiple CPU cores for heavy computation

1.3.3 Multiprocessing (Many Kitchens, Many Chefs)

The solution:

- Creates completely separate processes (kitchens)

- Each process = full copy with own memory

- Each has own GIL (own door lock)

- OS assigns processes to different CPU cores

- True parallel execution for heavy computational work

2 Parallel Computing Libraries in Python

2.1 Checking Your CPU Cores

Logical cores (total workers available to system):

import os

nombre_coeurs_logiques = os.cpu_count()

print(f"Number of logical cores: {nombre_coeurs_logiques}")

# Number of logical cores: 14Physical cores (actual computing units):

Install external library:

pip install psutilThen check:

import psutil

nb_cores = psutil.cpu_count(logical=False)

print(f"Number of physical cores: {nb_cores}")

# Number of physical cores: 142.2 Framework Comparison

We’ll compare 5 parallel processing approaches against sequential baseline:

1_single_process.py- Sequential baseline1_multiprocessing.py- Built-in multiprocessing module1_concurrent.py- concurrent.futures.ProcessPoolExecutor1_joblib.py- Joblib library1_mpire.py- MPIRE library

2.3 Library Details

2.3.1 1. multiprocessing

with Pool(workers) as p:

results = p.map(f, iterable)What it is:

- Python’s built-in solution for parallel execution on multiple cores

- Uses separate processes instead of threads

- Each process has own memory space and Python interpreter

Key feature:

- Enables true parallelism for CPU-heavy tasks

- Low-level API: Process, Pool, Queue

2.3.2 2. concurrent.futures

with concurrent.futures.ProcessPoolExecutor(max_workers=workers) as executor:

results = list(executor.map(f, iterable))What it is:

- High-level interface for thread/process pools

- Unified API for both threading and multiprocessing

- Returns Future objects as result placeholders

Key feature:

- Choose ThreadPoolExecutor or ProcessPoolExecutor

- Simple methods:

submit(),map() - Minimal code changes needed

2.3.3 3. joblib

results = Parallel(n_jobs=workers)(delayed(f)(i) for i in iterable)What it is:

- Third-party library for data science/scientific computing

- Optimized for NumPy arrays and large datasets

Key features:

- Smart caching (memoization), saves results to disk

- Memory mapping for large arrays

- Efficient data handling between processes

2.3.4 4. mpire (MultiProcessing Is Really Easy)

with WorkerPool(n_jobs=workers) as pool:

results = pool.map(f, iterable)What it is:

- High-performance library built on multiprocessing

- Enhanced version of multiprocessing.Pool

Key features:

- Built-in progress bars for long tasks

- Easy worker state management

- Performance optimizations

- Better developer experience

2.4 Running scripts

Use a virtual environment.

python -m venv adv_progYou can then activate your new env:

- On Windows: `adv_prog\Scripts\activate` - On macOS/Linux: `source adv_prog/bin/activate`Once activated, install all the library necessary using :

pip3 install -r requirements.txt

import time

from utils import f, workers, iterablerun_all_1.sh- Shell script to execute all parallel processing benchmarks

#!/bin/bash

for f in 1_*.py; do

echo "--- Running $f ---"

python3 "$f"

echo

echo "=============================="

done- This way we can just change the iterable and the function and rerun our comparisaon between paralelle computing libraries in python.

3 Benchmark Categories

3.1 1. I/O-Bound Tasks (Network Latency Simulation)

What it simulates:

- Network/database/API response waiting, No intensive computation, just waiting time

Results:

def f(x):

time.sleep(1)

return x*x

n= 25

iterable = range(n)

# --- Running 1_concurrent.py ---

# Took 3.080 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_joblib.py ---

# Took 3.125 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_mpire.py ---

# Took 3.034 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_multiprocessing.py ---

# Took 3.076 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_single_process.py ---

# Took 25.115 seconds

# ==============================

def f(x):

time.sleep(0.01)

return x*x

n = 2500

iterable = range(n)

# --- Running 1_concurrent.py ---

# Took 3.085 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_joblib.py ---

# Took 3.120 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_mpire.py ---

# Took 3.130 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_multiprocessing.py ---

# Took 3.075 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_single_process.py ---

# Took 25.099 seconds

# ==============================- All parallel frameworks perform similarly (~3s vs 25s sequential)

- CPU nearly idle during waiting periods

- OS switches between waiting tasks efficiently

3.2 2. CPU-Bound Tasks (Equal Duration)

What it simulates:

- Computation-intensive tasks (CPU-bound)

- Equal computation time per iteration

- Tests pure parallel computation distribution

Scenario:

- Prime number checking with fixed large number

Results:

def f(n):

n = 9999991

if n < 2:

return False

if n == 2:

return True

if n % 2 == 0:

return False

sqrt_n = int(math.floor(math.sqrt(n)))

for i in range(3, sqrt_n + 1, 2):

if n % i == 0:

return False

return True

n=1000

iterable = range(n)

# --- Running 1_concurrent.py ---

# Took 0.111 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_joblib.py ---

# Took 0.135 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_mpire.py ---

# Took 0.119 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_multiprocessing.py ---

# Took 0.051 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_single_process.py ---

# Took 0.037 seconds

# ==============================

n=100000

iterable = range(n)

# --- Running 1_concurrent.py ---

# Took 6.959 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_joblib.py ---

# Took 0.534 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_mpire.py ---

# Took 1.479 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_multiprocessing.py ---

# Took 0.447 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_single_process.py ---

# Took 3.761 seconds

# ==============================- Best performers: multiprocessing, joblib

- concurrent.futures: Higher-level abstractions introduce slight overhead

- Important: For n=1000, sequential (0.037s) beats parallel, process creation overhead exceeds time saved \(->\) Parallelization only worthwhile if tasks are long enough

3.3 3. CPU-Bound Tasks (Variable Duration)

What it simulates:

- Variable complexity across tasks

- Dynamic vs. static task distribution comparison. Some tasks fast (even numbers), others slow (large primes)

Scenario:

- Prime checking across range

Results:

def f(n):

if n < 2:

return False

if n == 2:

return True

if n % 2 == 0:

return False

sqrt_n = int(math.floor(math.sqrt(n)))

for i in range(3, sqrt_n + 1, 2):

if n % i == 0:

return False

return True

n=1000

iterable = range(n)

# --- Running 1_concurrent.py ---

# Took 0.108 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_joblib.py ---

# Took 0.096 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_mpire.py ---

# Took 0.118 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_multiprocessing.py ---

# Took 0.044 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_single_process.py ---

# Took 0.000 seconds

n=1000000

iterable = range(n)

# --- Running 1_concurrent.py ---

# Took 70.225 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_joblib.py ---

# Took 1.204 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_mpire.py ---

# Took 11.225 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_multiprocessing.py ---

# Took 0.147 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_single_process.py ---

# Took 0.863 seconds- Best performers: multiprocessing, joblib

- Dynamic task distribution: Send small chunks to workers; workers request new chunks when finished

- concurrent.futures (70s), divides tasks into large fixed chunks upfront

- Workers with long-running tasks create bottleneck while others sit idle

3.4 4. Disk I/O Operations

What it simulates:

- File system operations (read/write logs, dataset processing)

- I/O-bound tasks where disk speed is bottleneck

Scenario:

- File creation/deletion operations

3.4.1 Small files

import random

import string

import os

def f(x):

filename = f"{x}.txt"

path = 'data/'

letters = ''.join(random.choices(string.ascii_letters, k=200))

with open(path + filename, "w") as file:

file.write(letters)

os.remove(path + filename)

return filename

n = 1000

iterable = range(n)

# --- Running 1_concurrent.py ---

# Took 0.141 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_joblib.py ---

# Took 0.152 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_mpire.py ---

# Took 0.119 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_multiprocessing.py ---

# Took 0.118 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_single_process.py ---

# Took 0.099 seconds

# ==============================

n = 100000

iterable = range(n)

# --- Running 1_concurrent.py ---

# Took 8.297 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_joblib.py ---

# Took 7.609 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_mpire.py ---

# Took 7.312 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_multiprocessing.py ---

# Took 7.418 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_single_process.py ---

# Took 9.762 seconds3.4.2 Large files

def f(x):

filename = f"{x}.txt"

path = 'data/'

letters = ''.join(random.choices(string.ascii_letters, k=20000))

with open(path + filename, "w") as file:

file.write(letters)

os.remove(path + filename)

return filename

n = 1000

iterable = range(n)

# -- Running 1_concurrent.py ---

# Took 0.162 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_joblib.py ---

# Took 0.184 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_mpire.py ---

# Took 0.225 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_multiprocessing.py ---

# Took 0.140 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_single_process.py ---

# Took 0.630 seconds

# ==============================

n = 100000

iterable = range(n)

# --- Running 1_concurrent.py ---

# Took 10.911 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_joblib.py ---

# Took 8.809 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_mpire.py ---

# Took 10.175 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_multiprocessing.py ---

# Took 9.417 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_single_process.py ---

# Took 61.839 seconds

# ==============================- Bottleneck: Disk controller, not CPU

- Moderate gains: Processes compete for same physical resource (disk)

- Small files: Minimal/negative gain,write time so short that parallelization overhead dominates

- Large files: Clear benefit, longer write time allows parallel work and hides disk latency

3.5 5. Memory-Intensive Tasks

What it simulates:

- Memory consumption in multiprocessing, unlike multithreading (shared memory), multiprocessing duplicates resources

3.5.1 Small arrays

import numpy as np

def f(x):

size_in_mb = 500

num_elements = (size_in_mb * 1024 * 1024) // 8

big_array = np.random.rand(num_elements)

return len(big_array)

n = 100

iterable = range(n)

# --- Running 1_concurrent.py ---

# Took 2.660 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_joblib.py ---

# Took 1.822 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_mpire.py ---

# Took 2.086 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_multiprocessing.py ---

# Took 2.052 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_single_process.py ---

# Took 13.789 seconds

# ==============================3.5.2 Large arrays

def f(x):

size_in_mb = 5000

num_elements = (size_in_mb * 1024 * 1024) // 8

big_array = np.random.rand(num_elements)

return len(big_array)

n = 10

iterable = range(n)

# --- Running 1_concurrent.py ---

# Took 8.304 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_joblib.py ---

# Took 7.740 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_mpire.py ---

# Took 7.183 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_multiprocessing.py ---

# Took 7.253 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_single_process.py ---

# Took 13.624 seconds

# ==============================

- Gain from multiple cores generating arrays simultaneously

- RAM danger: Each process allocates memory independently

- joblib can optimize with memory mapping (not in this test)

3.6 6. Data Serialization Overhead

What it simulates:

- Inter-process communication (IPC) costs

- Serialization/deserialization overhead

- Python must serialize data (convert to byte stream via pickle) to send between processes

Scenario:

- Processing large NumPy arrays with inter-process communication

- Comparison includes vectorized NumPy operations

import numpy as np

def f(x):

return np.mean(x)

n = 100000

big_array = np.random.rand(100000000)

iterable =np.array_split(big_array, n)

# --- Running 1_concurrent.py ---

# Took 7.952 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_joblib.py ---

# Took 1.563 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_mpire.py ---

# Took 1.475 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_multiprocessing.py ---

# Took 0.985 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_single_process.py ---

# Took 0.162 seconds

# ==============================

matrix = big_array.reshape(n, -1)

means = matrix.mean(axis=1)

# -- Numpy

# Took 0.043 seconds

# ==============================

n = 1000

iterable = np.array_split(big_array, n)

# --- Running 1_concurrent.py ---

# Took 0.650 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_joblib.py ---

# Took 1.037 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_mpire.py ---

# Took 0.229 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_multiprocessing.py ---

# Took 0.865 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 1_single_process.py ---

# Took 0.034 seconds

# ==============================

# -- Numpy

# Took 0.026 seconds

# ==============================

- Best performers: Vectorized NumPy (0.043s), single_process (0.162s)

- Vectorized NumPy lesson: Operations executed in compiled C/Fortran code, if vectorization possible, try it!

- Serialization cost so high, faster to compute in one process than transfer data

4 GPU vs CPU for Matrix Operations

from Part 1: CPU parallelism is not efficient due to data transfer overhead between cores.

n = 100000

size = 100000000

big_array = np.random.rand(size)

iterable =np.array_split(big_array, n)

matrix = big_array.reshape(n, -1)

means = matrix.mean(axis=1)

# Took 0.033 secondsGPU solution for matrix operations:

import torch

import time

import numpy as np

if torch.cuda.is_available():

device = torch.device("cuda")

elif torch.backends.mps.is_available():

device = torch.device("mps")

else:

device = torch.device("cpu")

print("No GPU detected")

big_tensor = torch.rand(size, device=device)

t = time.time()

matrix_tensor = big_tensor.reshape(n, -1)

means_tensor = matrix_tensor.mean(dim=1)

# Took 0.003 seconds10x more data:

n = 100000

size = 1000000000

big_array = np.random.rand(size)

iterable =np.array_split(big_array, n)

matrix = big_array.reshape(n, -1)

means = matrix.mean(axis=1)

# Took 0.330 seconds (x10)

big_tensor = torch.rand(size, device=device)

t = time.time()

matrix_tensor = big_tensor.reshape(n, -1)

means_tensor = matrix_tensor.mean(dim=1)

#Took 0.005 seconds- NumPy scales almost linearly with data size

- GPU computation less than 2x slower despite 10x more data

4.1 GPU Architecture

Core concept:

- CPU: Few very powerful, smart cores

- GPU: Hundreds/thousands of simpler, specialized cores

Analogy:

- CPU: Head chef managing complex, overarching tasks

- GPU: Army of 1,000 kitchen assistants for repetitive tasks

- Task: Finely chop 10,000 carrots

- Process: Single command (“chop”) executed by all 1,000 assistants simultaneously

- Result: 10,000 carrots finished in time to chop just a few

GPU strength: Massive parallelism for simple, uniform tasks GPU limitation: Not suited for complex, varied operations

4.2 Benchmark: Cosine Similarity Search

Task: Find 3 most similar vectors for each new vector

3 approaches compared:

4.2.1 1. Pure NumPy

import time

import numpy as np

from utils_2 import nb_txt, dim, nb_new

def find_similar_numpy(new_texts_matrix, all_txt_matrix):

dot_product = np.dot(all_txt_matrix, new_texts_matrix.T)

all_txt_norm = np.linalg.norm(all_txt_matrix, axis=1)

new_texts_norm = np.linalg.norm(new_texts_matrix, axis=1)

denominator = all_txt_norm[:, np.newaxis] * new_texts_norm[np.newaxis, :]

similarity = dot_product / denominator

return np.argsort(-similarity, axis=1)[:, :3]

if __name__ == "__main__":

existing_txt_np = np.random.rand(nb_txt, dim).astype(np.float32)

new_txt_np = np.random.rand(nb_new,dim).astype(np.float32)

t = time.time()

closest_indices_np = find_similar_numpy(new_txt_np, existing_txt_np)

print(f"Took %.3f seconds" % (time.time() - t))4.2.2 2. PyTorch CPU

import torch

import time

import numpy as np

from utils_2 import nb_txt, dim, nb_new

device = torch.device("cpu")

def find_similar_pytorch(new_texts_tensor, all_txt_tensor):

dot_product = torch.matmul(all_txt_tensor, new_texts_tensor.T)

all_txt_norm = torch.linalg.norm(all_txt_tensor, dim=1)

new_texts_norm = torch.linalg.norm(new_texts_tensor, dim=1)

denominator = all_txt_norm.unsqueeze(1) * new_texts_norm.unsqueeze(0)

similarity = dot_product / denominator

return torch.argsort(similarity, dim=1, descending=True)[:, :3]

if __name__ == "__main__":

existing_txt_np = np.random.rand(nb_txt, dim).astype(np.float32)

new_txt_np = np.random.rand(nb_new,dim).astype(np.float32)

existing_txt_pt_cpu = torch.from_numpy(existing_txt_np)

new_txt_pt_cpu = torch.from_numpy(new_txt_np)

t = time.time()

closest_indices_pt_cpu = find_similar_pytorch(new_txt_pt_cpu, existing_txt_pt_cpu)

print(f"Took %.3f seconds" % (time.time() - t))4.2.3 3. PyTorch GPU

import torch

import time

import numpy as np

from utils_2 import nb_txt, dim, nb_new

if torch.cuda.is_available():

device = torch.device("cuda")

elif torch.backends.mps.is_available():

device = torch.device("mps")

else:

device = torch.device("cpu")

print("No GPU detected")

def find_similar_pytorch(new_texts_tensor, all_txt_tensor):

dot_product = torch.matmul(all_txt_tensor, new_texts_tensor.T)

all_txt_norm = torch.linalg.norm(all_txt_tensor, dim=1)

new_texts_norm = torch.linalg.norm(new_texts_tensor, dim=1)

denominator = all_txt_norm.unsqueeze(1) * new_texts_norm.unsqueeze(0)

similarity = dot_product / denominator

return torch.argsort(similarity, dim=1, descending=True)[:, :3]

if __name__ == "__main__":

existing_txt_np = np.random.rand(nb_txt, dim).astype(np.float32)

new_txt_np = np.random.rand(nb_new,dim).astype(np.float32)

existing_txt_gpu = torch.from_numpy(existing_txt_np).to(device)

new_txt_gpu = torch.from_numpy(new_txt_np).to(device)

t = time.time()

closest_indices_gpu = find_similar_pytorch(new_txt_gpu, existing_txt_gpu)

print(f"Took %.3f seconds" % (time.time() - t))4.3 Results Analysis

4.3.1 Small Scale Data

Parameters: nb_txt = 1000, dim = 100, nb_new = 100

# --- Running 2_numpy.py ---

# Took 0.002 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 2_pytorch_cpu.py ---

# Took 0.002 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 2_pytorch_gpu.py ---

# Took 1.196 seconds- CPU wins: Calculation trivial for modern CPU (milliseconds)

- GPU extremely slow: Data transfer overhead dominates

- Data must copy from RAM to GPU VRAM before computation

- Transfer time >> computation time for small data

- CPU accesses RAM almost instantly

4.3.2 Medium to Large Scale Data

Medium: nb_txt = 10000, dim = 100, nb_new = 1000

# --- Running 2_numpy.py ---

# Took 0.305 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 2_pytorch_cpu.py ---

# Took 0.054 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 2_pytorch_gpu.py ---

# Took 0.022 secondsLarge: nb_txt = 1000000, dim = 100, nb_new = 1000

# --- Running 2_numpy.py ---

# Took 30.882 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 2_pytorch_cpu.py ---

# Took 4.023 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 2_pytorch_gpu.py ---

# Took 0.026 seconds4.3.3 Scaling Dimensions and Vectors

Test 1: nb_txt = 100000, dim = 1000, nb_new = 1000

# --- Running 2_numpy.py ---

# Took 3.117 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 2_pytorch_cpu.py ---

# Took 0.444 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 2_pytorch_gpu.py ---

# Took 0.022 secondsTest 2: nb_txt = 100000, dim = 1000, nb_new = 10000

# --- Running 2_numpy.py ---

# Took 41.750 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 2_pytorch_cpu.py ---

# Took 5.713 seconds

# ==============================

# --- Running 2_pytorch_gpu.py ---

# Took 0.263 seconds- PyTorch CPU > NumPy: Built on optimized C++ libraries (MKL/OpenMP)

- Better parallelization across CPU cores

- Optimized execution model for larger tensors

- GPU dominates: Computation size hides data transfer latency

- Matrix multiplication is “embarrassingly parallel”

- Thousands of GPU cores vs. few CPU cores

- GPU time barely increases while CPU explodes

4.3.4 Memory Wall

Test: nb_txt = 100000, dim = 1000, nb_new = 100000

# --- Running 2_numpy.py ---

# ./run_all_2.sh: line 3: 35710 Killed: 9 python3 "$f"

# ==============================

# --- Running 2_pytorch_cpu.py ---

# ./run_all_2.sh: line 3: 35787 Killed: 9 python3 "$f"

# ==============================

# --- Running 2_pytorch_gpu.py ---

# Traceback (most recent call last):

# File "/Users/peltouz/Library/Mobile Documents/com~apple~CloudDocs/GitHub/Advanced Programming/2_pytorch_gpu.py", line 35, in <module>

# closest_indices_gpu = find_similar_pytorch(new_txt_gpu, existing_txt_gpu)

# File "/Users/peltouz/Library/Mobile Documents/com~apple~CloudDocs/GitHub/Advanced Programming/2_pytorch_gpu.py", line 18, in find_similar_pytorch

# dot_product = torch.matmul(all_txt_tensor, new_texts_tensor.T)

# RuntimeError: Invalid buffer size: 37.25 GiBKilled: 9 (CPU):

- OS Out Of Memory (OOM) killer terminated program

- Arrays too large for available RAM

- OS forcibly kills memory-hungry process to prevent system crash

RuntimeError: Invalid buffer size: 37.25 GiB (GPU):

- Matrix multiplication needs 37.25 GiB intermediate buffer

- Exceeds available VRAM on GPU

- GPU constraint: Entire dataset + model must fit in dedicated memory

- GPUs typically have less memory than system RAM

- Hit memory limits sooner for massive operations